Part III: Types of Bottle Closures

HOME:

Bottle Finishes & Closures: Types of closures

Click here to move to the Organization & Structure Summary for this page.

|

A bottle closure is, simply stated, the device that seals the contents inside of a bottle, protecting those contents from dust, spilling, evaporation, and/or from the atmosphere itself (Munsey 1970; Jones & Sullivan 1989). The finish and closure are interrelated entities of any bottle. The closure must conform to the finish in order to function, and vice versa. The invention of some closures correspond to certain finishes and a closure may be adapted to old finishes; or both the finish and closure are invented together (Berge 1980).

The use of bottles - and the need for varied closures to seal them - arose with an expanding city based market and even then for just a few types of bottled goods - primarily liquor, wine, and patent medicines in the early 19th century. As cities and relative affluence spread, the market and demand for bottled goods increased rapidly. At the same time, the expansion of the ever growing population into the farming regions of the Midwest created a need for methods and equipment to preserve foods. Thus, the need for canning jars. With the expansion of these demands came the need for suitable containers all of which had to be properly sealed to function. Parallel with the creativity of bottle & jar makers in satisfying this demand for glass containers, the creative juices of closure designers were unleashed. The thousands of different closure designs patented during the 19th century are a testament to that creativity, though most probably never made it into widespread manufacture (Lief 1965; Toulouse 1969a). This variety is illustrated later on this page with links to several dozen canning jars exhibiting a kaleidoscope of closure types most of which saw very limited popularity and use.

Closures are a useful subject to explore since the type of closure that a bottle had can often provide some dating refinement when used during a relatively narrow time frame. This is particularly true of canning jars and beer & soda bottles during the last half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Others, like the Lightning closure, was invented in the 1870s and is still in use today. Closures can also often assist in determining what type of bottle one has, i.e., what the bottle was most likely used for if (e.g., liquor, soda) it is not otherwise obvious.

Reference Notes: One of the better general references on closures is a small booklet entitled "A Close-Up of Closures: History and Progress" by Alfred Lief (1965), which was published by the Glass Container Manufacturers Institute, New York. In addition, a particularly useful recent (2016) work with an emphasis on commercial food bottles/jars is "Historic Bottle and Jar Closures" by Nathan Bender. The other primary references used for the preparation of this page included: Riley (1958), Toulouse (1969a), Munsey (1970), Ketcham (1975), Feldhaus (1986), Bender (1986), Elliott & Gould (1988), Jones & Sullivan (1989), Peters (1996), Fike (1998), Graci (2003), and others along with a lot of empirical observations over time. One other recent book still available and recommended - if one is particularly interested in bottle and jar closures - is:

|

This section covers closures that were used on a wide array of bottle types, i.e., closures which are generally not identified with only one or two types or classes of bottles. Inherently these closure types saw wide use for many types of bottles - implying higher than usual functionality - and because of that also experienced a long time span of use. This unfortunately limits the utility of the closure adding much refinement to the dating of a bottle that these closures are found on.

The earliest closure types for bottles were crude and variably effective. The following concise view of early closures is quoted from Dr. Julian Toulouse's book "Fruit Jars" (1969a):

There have been many kinds of closures for bottles, ever since glass and pottery have been used for container materials. Roman and Grecian containers used straw, rags, leather, and the like, luted (sealed) with clay, resins, natural waxes , and other binders. Some of those newly discovered had their closures intact. I well remember the potato that closed the spout of the coal-oil can, and the pottery jug of something or other that grandfather kept hidden in the barn, stoppered with a corn cob.

When home and commercial preparation and packaging of preserves, jams, and jellies started in the early 1700s with the greater availability of sugar, one closure method was simply a cover of waxed paper, cloth, parchment, leather, or skin, stretched across the opening, tied, and shorn off just below the tie. It was usually then dipped into hot wax. It was not paraffin as some have stated, because paraffin had not yet been discovered. Neither was this hermetic sealing to preserve sterility - the products involved did not need such protection, nor had the principle of heat sterilization itself been discovered. All that was needed was to keep the contents from drying out, and to keep them clean, as from dust and other unwanted materials.

These products did not need the more expensive, handcut, cork stoppers, and such closures were not immediately used. Traditionally the monk, Dom Perignon, cellerer and butler at the Benedictine Abbey at Hautvillers, France, from 1700 to 1715, is supposed to have started the use of whittled cork stoppers to hold the internal gas pressure of the wine that became known as champagne.

With that said we move on to the closures most commonly found on bottles made during the era covered by this website - the 19th through mid 20th centuries. The first is the ubiquitous cork closure, the use of which was at least partially pioneered by Dom Perignon.

The most common closure during the mouth-blown bottle era was the simple and highly effective cork

or cork stopper. Virtually all major bottle types from the

mouth-blown bottle era can be found with finishes that accepted some type of

cork closure, so there is little if any cork closure related typing utility for

mouth-blown bottles (empirical observations). Because of its

familiarity and versatility, the cork was popular well into the machine-made

bottle era of the early 20th century (Illinois Glass Co. 1920; Obear-Nester

Glass Co. 1922; Bender 2016).

The most common closure during the mouth-blown bottle era was the simple and highly effective cork

or cork stopper. Virtually all major bottle types from the

mouth-blown bottle era can be found with finishes that accepted some type of

cork closure, so there is little if any cork closure related typing utility for

mouth-blown bottles (empirical observations). Because of its

familiarity and versatility, the cork was popular well into the machine-made

bottle era of the early 20th century (Illinois Glass Co. 1920; Obear-Nester

Glass Co. 1922; Bender 2016).

Cork comes from the bark

of the cork oak tree (Quercus

suber and Q. occidentalis) and is still, of course, in use today.

Cork as a stopper for vessels goes back to antiquity, being mentioned for such

use by the Greek author Pliny the Elder during the first century A. D. (Faubel

1938). The elasticity of cork

- the ability to assert its normal size after compression - was its primary attribute allowing

it to be squeezed into the bore of a bottle and create a seal (Faubel 1938; Jones & Sullivan

1989). In addition, its chemical inertness made it ideal for sealing

almost any type of bottled product - liquid or solid - while imparting no flavor

to that product (Faubel 1938). Cork when kept moist by the contents of the

bottle would also stay plumper and maintain its seal over a long time, which is one of

the reasons

cork is still used for wine bottles today (Riley 1958). The properties of cork

were perfect for the irregularly formed mouths of mouth-blown bottles which had

finishes that were hand tooled with a commensurate lack of precision. The

author of this website has many cork sealed bottles which are well over 100

years old but still have their contents virtually totally intact. (Cork

being somewhat porous does breathe ever so slightly so some evaporation occurs over a

long period of time even though securely sealed.) Corks were soaked in

water and then squeezed into the proper shape for insertion in bottles with a tool called a "cork press" - see the illustration

to the left (Richardson 2003). Click

cork press for a picture of an ornate, late 19th century, small hand operated cork

press.

which are well over 100

years old but still have their contents virtually totally intact. (Cork

being somewhat porous does breathe ever so slightly so some evaporation occurs over a

long period of time even though securely sealed.) Corks were soaked in

water and then squeezed into the proper shape for insertion in bottles with a tool called a "cork press" - see the illustration

to the left (Richardson 2003). Click

cork press for a picture of an ornate, late 19th century, small hand operated cork

press.

The following is from Holscher (1965, from Berge 1980) about the early history of cork:

While wax and resin mixtures were used in the 15th century as a stopper, the cork is also mentioned in English literature in the early 1500s for the same purpose, in connection with bottles. And it was the stopper which permitted the development of the true champagne.

The cork was not immediately "tied-on" in the early period for, in England, at least, the wired-on cork dates from 1675-1700. In the early champagne and wine days, the corked (sealed) bottle section was inverted in a wax, compound, or oil to coat the cork; the seal was thus improved. Wax stoppers, used in Mid-Continental Europe for alchemy and medicine, were replaced by tight corks after the latter's discovery. Thus, corks became the common bottle stopper during a 300 year period, from early development before 1600 to almost complete use following 1900.

Corks were also used extensively during the early part of the fully automatic machine-made bottle era, i.e., 1905 into the 1920s when cork's reign of dominance really began to run out (Lief 1965). The bottle pictured to the above left is a 1920s era machine-made bottle made during the transition time when corks were still very common on medicinal bottles like this one from Atlanta, GA. which was made by a glass company in Chattanooga, TN. (Click S.S.S. bottle to view a picture of this entire bottle.)

|

The top illustration shows a cork finish (i.e., cork accepting) on a prescription druggist bottle. The bottom illustration shows the same type bottle with a screw thread finish with the metal cap on. These illustrations are from a 1928 Owens Bottle Company "Want Book and Catalog of Owens Bottles...for Druggists". This catalog shows the availability of both closure types from the same manufacturer in the late 1920s with the note that the screw caps are "...growing more popular every day." The company (the Owens-Illinois Glass Co. after 1929) still offered cork finishes on prescription bottles until at least the early 1940s, though much diminished in importance in their catalogs. |

Because of this wide span of use and popularity, the presence of a cork accepting finish is not indicative of age for the majority of bottles made up until at least the 1920s - mouth-blown or machine-made. The utility of cork closures for dating is that certain types of machine-made bottles made the transition from cork accepting to screw-thread (or other non-cork) finishes primarily from the 1920s into the mid-1930s; see the 1928 illustrations to the left (Berge 1980; empirical observations). The bottle types that mostly made the switch during this era are a large majority of medicinal/druggist, food, and ink bottles; the majority of liquor/spirits bottles; and some non-alcoholic, non-carbonated beverage bottles, though there are exceptions with just about all these categories. Cork is still commonly used for sealing bottles containing wine and champagne, occasional "higher end" liquor/spirits bottles (i.e., single malt Scotch), and rarely some specialty food product bottles.

Corks

were held in place in a lot of different ways. The most common and easiest

method was simply the compression induced friction of the cork against the

inside of the bottle bore and sometimes upper neck. An additional sealing

safeguard entailed the placement of a lead or foil wrapper

or "capsule" over the upper neck, finish and cork much like champagne

and some liquor bottles are sealed today. This foil wrapping held the cork

quite firmly in place for most non-carbonated liquids and helped seal the bottle

from the atmosphere. A capsule by itself would be inadequate for

carbonated products; wire was often used under the capsule to more fully secure

the cork.

Corks

were held in place in a lot of different ways. The most common and easiest

method was simply the compression induced friction of the cork against the

inside of the bottle bore and sometimes upper neck. An additional sealing

safeguard entailed the placement of a lead or foil wrapper

or "capsule" over the upper neck, finish and cork much like champagne

and some liquor bottles are sealed today. This foil wrapping held the cork

quite firmly in place for most non-carbonated liquids and helped seal the bottle

from the atmosphere. A capsule by itself would be inadequate for

carbonated products; wire was often used under the capsule to more fully secure

the cork.

The picture to the right shows an alcohol laced (18%) medicinal bottle (Ferro-China-Berner Tonic) with the full contents and sealed with a foil capsule over the cork. This bottle dates from the early 20th century. Click Ferro-China-Berner tonic bottle to view a picture of this entire bottle, which the label states is from New York, though the bottle (and possibly contents) were probably manufactured in Europe. A similar cork sealing method was to dip the corked finish in hot wax instead of a foil wrapper (Jones & Sullivan 1989).

With carbonated beverages (soda, beer, champagne) the cork had to be

secured more positively to prevent the content pressure from loosening the cork

and slowly leaking the carbonation or even popping out prior to consumption of

the contents. To accomplish this some type of tightened wiring or strong

cord or string was wrapped in various ways around the upper neck and finish area

with a portion looping over the cork to maintain it securely in the bottle.

The picture to the lower right shows an

early 20th century (1900-1910)

King's Pure Malt "beer tonic" bottle (Boston, MA.) with a

blob finish and the cork in place.

Though somewhat loose now, the wire that held the cork secure is also still present. The upper,

thicker wire looped over the top of the cork (which was pushed in level with the

top of the bore) and was held tightly in place by

the smaller wires tightly (originally) encircling the neck just below the lower portion of the

finish. This type closure is called a "wired cork stopper."

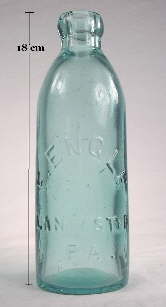

Another popular type of simple cork retainer was the more solid wire Henry

Putnam patented (1859) design as pictured below. This type wire bail had

the benefit of being reusable and was particularly popular on soda and mineral

water bottles during the 1860s through 1880s like the

Hoffman & Joseph "blob-top" soda pictured which dates from the mid-1880s

(Fowler 1981). The utility of the blob type finish was that it provided a

large ridge for properly securing the wire below the finish. Many

variations on these basic

themes can be found on 19th and early 20th century cork sealed bottles (Lief

1965; Jones & Sullivan 1989; Graci 2003).

(NOTE: Without the original

closure still in place, it is not often possible to tell if a given blob

finished bottle utilized a cork as the closure or some other type, like a

Lightning closure (covered later) which has disappeared. For example, the

bottle to the right could have initially been sealed with a Lightning stopper

which was used until it became non-functional or removed, then refilled and

corked with a simple wire to hold the cork in place. The first

Lightning-type stoppered bottle covered in that section below has the same

finish as the malt tonic bottle to the right. Without the original

closures in place, one can not state for sure what the closure was.)

(NOTE: Without the original

closure still in place, it is not often possible to tell if a given blob

finished bottle utilized a cork as the closure or some other type, like a

Lightning closure (covered later) which has disappeared. For example, the

bottle to the right could have initially been sealed with a Lightning stopper

which was used until it became non-functional or removed, then refilled and

corked with a simple wire to hold the cork in place. The first

Lightning-type stoppered bottle covered in that section below has the same

finish as the malt tonic bottle to the right. Without the original

closures in place, one can not state for sure what the closure was.)

Besides the frequent inadequate sealing problems, cork had several other problems that slowly led to its demise. One was that it was often difficult to initially unseal the bottle with the cork intact and unbroken so that it could be used to reseal the partially utilized contents of the bottle. This is still a problem with wine bottles and has lead to numerous innovative and non-destructive cork removing tools in recent decades. Also, the process of bottling and sealing with a cork was slow and inefficient. The following is quoted from David Graci's recent book (2003) entitled Soda and Beer Closures 1850-1910. It outlines the laborious efforts of hand corking early carbonated beverage bottles which was likely similar to the bottling of any product in cork closured bottles:

An early method of bottling carbonated drinks was called "Hand and Knee Bottling", and involved an operator who sat at a hand operated bottle filling machine. Holding a bottle to the machine he raised a board under his knee, pressing the bottle's mouth to a tight fit and manually filling it, allowing excess pressure out before inserting a cork, which was then driven into the bottle with a wooden mallet. In this manner 200 dozen bottles a day could be filled by a skilled knee bottler..."

Undoubtedly, that mallet strike broke many bottles. It was this type of relatively slow, labor intensive method in hand with the other noted problems of cork that lead many pioneering inventors to thinking and tinkering towards making both better closure types and machines to speed up and make more safe the process of bottling products. Though cork was effective, most of the early closure efforts by inventers and bottlers were directed at finding a substitute for cork (Graci 2003). The rest of this page discusses some of the more successful "substitutes."

One of the most common, non-cork closures is the large and

diverse group of threaded closures. They come in both externally threaded

and internal threaded versions. The internal or inside thread closures

have a couple main variations that are fairly similar except for the materials the

closures are made from: primarily hard rubber or glass. The closures for externally threaded finishes vary

widely and are made from many materials - typically various metals and more

recently plastic, but on occasion glass, rubber,

and likely others. Externally threaded closures (and related finishes) are

arguably the most significant closure method of all time given that is has had

one of the longest runs of any closure method with ubiquity to this day.

Internal Threaded

Stopper/Closure

Internal Threaded

Stopper/Closure

The distinctive feature of this

closure/finish combination is the continuous type threads which are found on the

inside of the finish. The outside of the finish looks similar to

other finishes of the era. There were two primary types of internal or inside

threaded closures: hard rubber and glass. Both are covered separately below.

Hard Rubber: This closure/finish is by far most commonly found on U.S. made mouth-blown, tooled finish liquor bottles produced between the late 1880s and National Prohibition in 1920; and in particular between 1895 and 1915 (Wilson & Wilson 1968; Root 1990). The tooled inside thread finish to the left (inside of a "straight brandy" finish) is on an S. A. Arata & Co. (Portland, OR.) pint flask that dates between 1905 and 1911 (Thomas 1998a). Inside thread finishes on flasks were much less common than on cylinder fifths and quarts of that era, but common enough to warrant mention here. The amber tooled inside thread finish (what would otherwise be called a brandy finish without the threads) below left is on an Old Castle Whiskey (San Francisco, CA) that was, according to Wilson & Wilson (1968), produced by the F. Chevalier Company between 1895 and 1901. This is an era typical inside threaded cylinder liquor bottle.

(Note: This Old Castle Whiskey bottle is also embossed with the maker's mark P. C. G. W. on the base for the Pacific Coast Glass Works (San Francisco, CA.) which did not commence operations until 1902 (Toulouse 1971). This allows for an earliest manufacture date of 1902, outside of the Wilson's range. Toulouse's date is considered more accurate than Wilson's date range which was their best estimate at that time, pre-dating Toulouse's publication by 3 years. This is and example of why - if possible - it is wise to consult several sources to confirm date ranges for bottles. Unfortunately, many or most bottles don't provide the luxury of multiple information sources.)

This era's bottles

usually had the standardized hard rubber type stopper with rounded and somewhat vague thread ridges as shown close-up in the picture to the

right (Wilson & Wilson 1968; Munsey 1970). The stoppers also included a softer rubber gasket

right below the head of the stopper which sealed against the rim of the finish (missing on the pictured stopper). These are much easier to screw tight (and

unscrew) than the inside thread stopper noted next. During this era a few other types of bottles were made

with inside thread finishes including some soda/mineral waters (most were foreign

- English - made),

chemical and/or ammonia bottles, perfumes and colognes, some ink bottles, and

even some baby nursing bottles (Elliot & Gould 1988; empirical

observations).

This era's bottles

usually had the standardized hard rubber type stopper with rounded and somewhat vague thread ridges as shown close-up in the picture to the

right (Wilson & Wilson 1968; Munsey 1970). The stoppers also included a softer rubber gasket

right below the head of the stopper which sealed against the rim of the finish (missing on the pictured stopper). These are much easier to screw tight (and

unscrew) than the inside thread stopper noted next. During this era a few other types of bottles were made

with inside thread finishes including some soda/mineral waters (most were foreign

- English - made),

chemical and/or ammonia bottles, perfumes and colognes, some ink bottles, and

even some baby nursing bottles (Elliot & Gould 1988; empirical

observations).

This style of closure/finish combination appears to have been used most commonly on liquor bottles from Western American companies made between 1895 and 1915, though inside threads are known on occasional liquor bottles on the Eastern Seaboard - most notably on the South Carolina Dispensary bottles (Wilson & Wilson 1968; Teal & Wallace 2005). Most if not all of these hard rubber stoppers were made in England and imported for use on American made bottles (Jones 1961). This type of threaded stopper/finish was also very common on English ale and mineral water bottles during the same general era - mid to late 19th to early 20th century - though not covered by this website. The finishes that accepted this type of stopper on American made bottles are almost always tooled finishes, though there some exceptions which have Western American product identification embossed on them but have applied finishes. These were likely foreign made and imported (Thomas 2002).

Glass: An earlier and less common

type of inside thread finish/closure which utilized a threaded glass stopper

was used primarily on liquor bottles and flasks dating from 1861 to probably

the late 1870s.

The

applied inside thread finish (inside of a "straight brandy" finish) in the two pictures

here are on a

Weeks & Potter (Boston, MA) liquor bottle that dates between 1861 and

about 1870.

This bottle has the Samuel A. Whitney

patented (Patent

#31,046, January 1, 1861) inside thread finish that accepts a glass

threaded stopper. The patent noted that this finish arrangement was "...applicable

to a variety of bottles and jars...(but) is especially well adapted to and has been more especially designed for use in connection with

mineral-water bottles, and such as contain effervescing wines, malt liquors,

&c..." (McKearin & Wilson 1978; U. S. Patent Office 1861).

A later, subtle variation of this type closure and finish was patented in

1872 by Himan Frank (one of the sons of the William Frank & Sons Glass

Company [Pittsburgh, PA.]) and was comprised of two patents - one for

the finish and stopper (Patent

#130,208) and one for the tool that formed the finish (Patent

#130,207) (U. S. Patent Office 1872; Lockhart et al. 2008b). In

the experience of the author, bottles with the Frank closure and finish are much

less common than the Whitney version.

The

applied inside thread finish (inside of a "straight brandy" finish) in the two pictures

here are on a

Weeks & Potter (Boston, MA) liquor bottle that dates between 1861 and

about 1870.

This bottle has the Samuel A. Whitney

patented (Patent

#31,046, January 1, 1861) inside thread finish that accepts a glass

threaded stopper. The patent noted that this finish arrangement was "...applicable

to a variety of bottles and jars...(but) is especially well adapted to and has been more especially designed for use in connection with

mineral-water bottles, and such as contain effervescing wines, malt liquors,

&c..." (McKearin & Wilson 1978; U. S. Patent Office 1861).

A later, subtle variation of this type closure and finish was patented in

1872 by Himan Frank (one of the sons of the William Frank & Sons Glass

Company [Pittsburgh, PA.]) and was comprised of two patents - one for

the finish and stopper (Patent

#130,208) and one for the tool that formed the finish (Patent

#130,207) (U. S. Patent Office 1872; Lockhart et al. 2008b). In

the experience of the author, bottles with the Frank closure and finish are much

less common than the Whitney version.

These earlier glass inside thread stoppers have much more distinct thread ridges than the later rubber stoppers. This made it a bit harder to screw tight (as well as unscrew) from the finish. Click Whitney glass stopper for a close-up picture of the glass stopper showing the patent date embossed on the top (the stopper is about 3 cm long). As with the hard rubber stopper, these had a soft rubber gasket just below the top cap part of the stopper, that sealed against the top surface of the finish. Weeks & Potter was a Boston proprietary medicine (and apparently liquor) concern, founded in 1852 and operating well into the 20th century (Odell 2000:92). These bottles most definitely held liquor as labeled ones have been observed by the author noting that they contained "Old Bourbon Whiskey."

This stopper is seen rarely

on U. S. produced mineral

water and/or ale bottles and even on at least one bitters bottle - Old

Homestead Wild Cherry Bitters (Ring & Ham 1998; Graci 2003). It is

most often observed (though rarely seen overall) on pint & half pint liquor

flasks as well as tall cylinder liquor bottles like the Weeks & Potter

bottle, all of which often (but not always) have Whitney

Glass Works embossed on the base. Images of a pint union oval type flask with

WHITNEY GLASS WORKS embossed on the base is available at the following

links:

Whitney Glass Works pint flask;

close-up pictures of the

base, finish,

and stopper. Glass inside thread stoppers

were occasionally used on English nursing bottles; click

English nursing bottle for a picture of an example.

External

Threaded Screw Cap

External

Threaded Screw Cap

The external threaded finish/closure combination is

one of the most common bottle closures of the 20th century and has a wide array of variations. This ubiquitous finish/closure

combination is distinguished

by having some type of raised ridge or ridges on the outside surface of the

finish that accepted an appropriately shaped cap which tightened and sealed

the bottle when twisted. External thread finishes are so

commonly used today that further explanation is probably not necessary;

everyone is familiar with "screw-top" bottles. For more

information on some of the varieties of externally threaded finishes and their

closures, click

Bottle Finishes & Closures: Part II: Types or Styles of Finishes.

That information is not repeated here since the major differences between

varieties is related more to the finish conformation than the cap.

|

Plastic caps for

external threaded finishes: an excellent bottle dating feature! Plastic caps for screw thread finishes can be an excellent tool for bottle dating. Bakelite - an early thermosetting plastic - made its debut in 1927 as a screw cap closure material though was first patented in 1907 (Berge 1980). This provides a terminus post quem (earliest date of use) of 1927 for bottles with the plastic cap still present. The illustration above is from a 1932 Owens-Illinois Glass Co. (Toledo, OH.) druggist bottle catalog showing green glass (the same green glass used for the jar to the right) dropper bottles with a "molded cap." |

The flask pictured above - with cap in place and cap removed - is a mouth-blown bottle on which the mold formed the threads. Click external screw thread flask to view an image of this entire liquor flask. The rough top surface of the finish, where the blowpipe was removed, was ground down flat to facilitate sealing between the cork liner on the inside top flat surface of the cap and the top of the finish. This flask dates from just before National Prohibition went into effect in 1920, as it is maker marked ("M" in a circle) on the base by the Maryland Glass Co., Baltimore, MD. (Toulouse 1971). (Note: This flask also originally had a shot cup screw cap that was placed over the cap shown and tightened down on the screw threads that are just below the bottom of the small cap. See the Double Screw Thread closure section at the bottom of this page for more information.) Outside of canning and some other food type jars, liquor flasks, and a few other styles, mouth-blown bottles with external screw thread finishes are unusual. Click on the following link - true applied external screw cap finish - for a discussion of a very unusual true applied finish with external screw threads - an extremely uncommon occurrence.

By about 1920, machines dominated the production of bottles (Barnett 1926). The higher levels of precision attainable with automatic bottle machines and the adoption of industry-wide standards for external thread finishes and metal screw cap closures between 1919 and 1924 spelled the end of cork as the dominant closure type (Lief 1965). Externally threaded bottles probably dominated the market by the late 1920s with cork sealed bottles becoming increasing more uncommon after that date with the exception of wine bottles, many liquor bottles, and bottles sealed with the revolutionary crown caps (Lief 1965). See the box to the left for information on plastic screw caps for bottles.

The

machine-made external threaded finish/closure combination pictured to the

right - with and without the metal cap on - is on an

ointment jar that was produced by the Owens-Illinois Glass Company

in 1940 based on the mold markings on the base. These jars were

produced at least as

early as 1935 and probably continued to be manufactured through the 1940s

(Owens-Illinois Glass Co. 1935).

The

machine-made external threaded finish/closure combination pictured to the

right - with and without the metal cap on - is on an

ointment jar that was produced by the Owens-Illinois Glass Company

in 1940 based on the mold markings on the base. These jars were

produced at least as

early as 1935 and probably continued to be manufactured through the 1940s

(Owens-Illinois Glass Co. 1935).

The dating of bottles with external

screw thread closures follows, of course, the dating for the finish it fits.

For more dating information, click

Bottle Finishes & Closures: Part II: Types or Styles of Finishes to

view the portion of that page (#16 "small mouth external threads" and #17

"wide mouth external threads") which discusses the general dating of

various types of external

screw thread finishes/closures on different types of bottles and jars.

Click here to return to the page content links box above.

The

"Lightning" toggle or swing-type closure is covered under this section because of its

widespread use on a lot of different bottle types, though its primary

application was for carbonated beverages (soda, beer) and canning jars (both

also covered

later on this page). The sealing surface for these two main types of

Lightning-type closures was different; that information is found below. There have been many subtle variations and imitations of this

style; thus

the reference to "Lightning-type" closure. This important closure was

invented and patented first by Charles de Quillfeldt of New York City on January

5, 1875. The design was intended initially for beverage bottles.

The

"Lightning" toggle or swing-type closure is covered under this section because of its

widespread use on a lot of different bottle types, though its primary

application was for carbonated beverages (soda, beer) and canning jars (both

also covered

later on this page). The sealing surface for these two main types of

Lightning-type closures was different; that information is found below. There have been many subtle variations and imitations of this

style; thus

the reference to "Lightning-type" closure. This important closure was

invented and patented first by Charles de Quillfeldt of New York City on January

5, 1875. The design was intended initially for beverage bottles. Click

Charles de Quillfeldt's Bottle-Stoppers Patent #158,406 to see the original

patent (U. S. Patent Office).

Click

Charles de Quillfeldt's Bottle-Stoppers Patent #158,406 to see the original

patent (U. S. Patent Office).

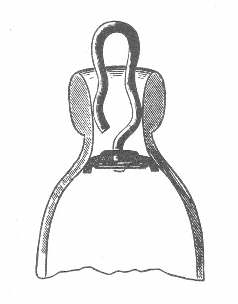

To quote Toulouse (1969a) about the de Quillfeldt patent: "This patent covered all the basic details. The seal was composed of a neck tie-wire, a lever wire, and a bail. The bail passed through a hole in the metal, rubber faced, lid. The lever wire was hooked into loops in the heavy neck tie-wire on opposite sides of the bottle. Movement of the lever wire past the line of centers of force was stopped by the neck of the bottle." Looking at the picture to the left while reading this description is helpful. The illustration to the right shows the configuration of the closure without the bottle (Lief 1965, courtesy of the Glass Container Manufacturers Institute). The actual "stopper" or lid portion of this closure was usually made from either metal (true Lightning closure) or porcelain/ceramic (Hutter style discussed below) with a round rubber gasket attached to the shank of the stopper to seal the bottle (gasket shows in picture below). The picture above is of a classic Lightning closure with a metal lid with the gasket missing on a Buffalo Brewing Company bottle (Sacramento, CA.) with a tooled blob finish that dates between 1890 and 1902 (Toulouse 1971; Groff 2002). Note: on this website the Lightning and Hutter type swing stoppers are just called Lightning or Lightning type.

Shortly

after patenting the design, de Quillfeldt sold the patent rights to several

individuals, including Henry Putnam (for fruit jars primarily) and Karl

Hutter (for beverage bottles; transferred June 5th, 1877). The history of competing designs,

contentiousness, and lawsuits between these and other individuals using this

basic form of closure is fascinating, but beyond the scope of this website.

See Toulouse (1969a) or Graci (2003) for more information on this subject.

Pictured to the left is a Lightning-type closure, on a pint beer bottle of a

style common between 1890 and 1915, which is marked on the underside of the

ceramic stopper with "Hutter's Patent" which is likely related to a

later (1892) Hutter patent based on the original design. (Click

Karl Hutter's Bottle Stopper Patent #491,113 to see this patent.) The sealing surface for small bore

(beverage type) Lightning-type closures was the rim (top surface) of the

finish and extreme

upper portion of the bore just inside the bottle; where the rubber gasket

shows to the left. As one can see in

comparing the Hutter closure with the other two pictured beer bottles, there are no real functional

differences between them. Click

W. E. Earl beer bottle to view a picture of the entire beer bottle (W.

E. Earl / Newton, N.J.) with the Hutter closure.

Shortly

after patenting the design, de Quillfeldt sold the patent rights to several

individuals, including Henry Putnam (for fruit jars primarily) and Karl

Hutter (for beverage bottles; transferred June 5th, 1877). The history of competing designs,

contentiousness, and lawsuits between these and other individuals using this

basic form of closure is fascinating, but beyond the scope of this website.

See Toulouse (1969a) or Graci (2003) for more information on this subject.

Pictured to the left is a Lightning-type closure, on a pint beer bottle of a

style common between 1890 and 1915, which is marked on the underside of the

ceramic stopper with "Hutter's Patent" which is likely related to a

later (1892) Hutter patent based on the original design. (Click

Karl Hutter's Bottle Stopper Patent #491,113 to see this patent.) The sealing surface for small bore

(beverage type) Lightning-type closures was the rim (top surface) of the

finish and extreme

upper portion of the bore just inside the bottle; where the rubber gasket

shows to the left. As one can see in

comparing the Hutter closure with the other two pictured beer bottles, there are no real functional

differences between them. Click

W. E. Earl beer bottle to view a picture of the entire beer bottle (W.

E. Earl / Newton, N.J.) with the Hutter closure.

Other Lightning-type toggle closures with variably subtle differences

though still with the toggle portion at the lower part of the finish or

upper neck, were patented by F. Perry (1878), N. Fritzner

(1880), E. Manning (1896), L. Brome (1899), J. Alston (1900), F. Thatcher

(1901), M. Landenberger (1901), W. Cunningham (1901), L. Strebel (1903), and

others. Closure names included the "Electric" (1889), "Pittsburgh"

(1889), "Porcelain-special" (date unknown), and others (Berge 1980). All of these variations saw some limited use during the

same period as the "true" Lightning (including the Hutter) closures. The bottles these

Lightning type closures are found date in the same range, though likely closer to the actual patent

date since none received the widespread acceptance of the original Lightning.

During this same era there were numerous related closures that utilized a

toggle or "lever" on top of the closure instead of below like with the

Lightning-types. Click

Walker Patent stopper for an example of one - the James T. Walker 1885 patented closure. For

more information on soda & beer closures, see Graci's book (Graci 2003).

Lightning-type swing closures were most popular on beer and many soda bottles from the 1880s into the 1920s. Use after that time was limited though occasional. The bottle/closure pictured to the right is a modern Grolsch® Lager (Dutch) bottle having a pretty "classic" Lightning-type closure. That company's current marketing internet site calls it the "Swingtop" closure and notes that it has been used by them since 1897 (Grolsch® website: http://www.grolsch.com). The only difference between the "Swingtop" and Lightning-type closures is that the "Swingtop" has no neck encircling wire. Instead the closure is attached to the finish via two dimple holes on opposite sides of the lower finish. Lightning-type closures are also found today on various foreign beer bottles, some decorative storage bottles & jars sold in "import" stores, and likely other bottle types. The lid portion of modern Lightning-type closures are usually made from plastic but still have the rubber gasket for sealing.

One of the best known Lightning-type variations is the closure found on canning jars (pictured below). Though the term "Lightning" was used by de Quillfeldt in reference to the sealing method, its application and use on fruit jars gave rise to the actual name of the Lightning fruit jar and the popularity of the term for the closure. The sealing surface for the Lightning closure on fruit jars was the shelf that the lower edge of the lid sat on; a rubber gasket was placed between that shelf and the bottom surface of the glass lid which when the closure is tightened forming a seal.

Henry Putnam's contribution to this world is that he slightly altered the

original de Quillfeldt design in

that the bail is not actually attached to the lid, which would not work on

wide mouth jars. Instead, the lid is held in position by

centering the bail in a groove or between two raised dots in the center of

the lid.

This securing point has been called a

cover groove (White 1978). The other

minor difference is that two metal "eyes" replaced the loops on the tie-wire as

fulcrums for the lever wire. In collaboration with de Quillfeldt,

Putnam patented this closure

in 1882. Click

Lightning jar closure and lid for a close-up picture

that shows the cover groove and one of the metal "eyes" (visible on upper part of

tie-wire) on a quart sized Lightning fruit jar. Click

Henry Putnam's Stopper for Jars Patent #256,857 to see the original patent

for this specific jar closure (U. S. Patent Office). The linked patent

illustrations also show well the conformation and functioning of the Lightning

closure. Though not as ubiquitous as the Mason screw thread type jars, Lightning jars were

quite popular with home canners and

date from 1882 to the early 1900s. "PUTNAM" - for Henry

Putnam - is embossed on the base

of most Lightning canning jars. Lighting-type closures are found on

various fruit jars made from as early as the late 1870s until at least the

mid-20th century (Toulouse 1969a; Creswick 1987).

Henry Putnam's contribution to this world is that he slightly altered the

original de Quillfeldt design in

that the bail is not actually attached to the lid, which would not work on

wide mouth jars. Instead, the lid is held in position by

centering the bail in a groove or between two raised dots in the center of

the lid.

This securing point has been called a

cover groove (White 1978). The other

minor difference is that two metal "eyes" replaced the loops on the tie-wire as

fulcrums for the lever wire. In collaboration with de Quillfeldt,

Putnam patented this closure

in 1882. Click

Lightning jar closure and lid for a close-up picture

that shows the cover groove and one of the metal "eyes" (visible on upper part of

tie-wire) on a quart sized Lightning fruit jar. Click

Henry Putnam's Stopper for Jars Patent #256,857 to see the original patent

for this specific jar closure (U. S. Patent Office). The linked patent

illustrations also show well the conformation and functioning of the Lightning

closure. Though not as ubiquitous as the Mason screw thread type jars, Lightning jars were

quite popular with home canners and

date from 1882 to the early 1900s. "PUTNAM" - for Henry

Putnam - is embossed on the base

of most Lightning canning jars. Lighting-type closures are found on

various fruit jars made from as early as the late 1870s until at least the

mid-20th century (Toulouse 1969a; Creswick 1987).

| Lockhart, Bill, Beau Schriever, Bill Lindsey and Carol Serr. 2016h. Henry W. Putnam and the Lightning Fastener. Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website, E-published June 2016. Article on the history, products and markings for this well known mid 19th to early 20th century inventor and company. This article is available at this link: http://www.sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/HenryPutnam.pdf This article is part of the Encyclopedia of Manufacturers Marks on Glass Containers. |

As noted, Lightning-type closures were utilized most

commonly on carbonated

beverage bottles and canning jars. The beauty of this closure on the

carbonated beverage bottles of the era is that it was adaptable to the

existing cork accepting finish bottles (typically with mineral and blob

finishes) and did not need entirely new bottles to function correctly, like

some other closures covered below. This closure has been observed occasionally on

other types of bottles including most

citrate of magnesia bottles, some

ginger beer bottles (glass or crockery), and very rarely bitters, liquor, wine, and

a few other bottles. The pre-dominant period of use for all of these

types of bottles with the Lightning-type closure was from the 1880s

through at least the late 1920s (Illinois Glass Company 1920, 1928;

empirical observations). Given the wide

utilization of this type closure over a long period of time, there is

limited dating or typing (i.e., what a bottle contained) information to be

gained from the presence of this closure; other manufacturing based diagnostic features must be

utilized. One exception is that if a bottle is known to date in the

above date range and has a narrow mouth Lightning-type closure (i.e., not a

canning jar), it is highly likely that it held either beer, soda water, or

possibly citrate of magnesia. (Note: Citrate of magnesia bottles have

a fairly distinctive shape; see the

Bottle Typing/Diagnostic Shapes page for more information.)

Generally speaking, a stopper is any closure which fits inside the neck (bore) of a bottle to make a seal, rather than on top of the finish - like a crown cap - or around the outside of the finish, like a screw cap (White 1978). The use of stoppers as closures for bottles dates back to antiquity, with some glass ones dating back as early as 1500 B.C. (Holscher 1965). Ground glass stoppers appeared in the U.S. by 1790 though the serious use of glass as a stopper - especially for food containers - began in the U.S. during the 1840s and 1850s (Bender 1986). In the bottle world, the term stopper is often used in reference to non-cork type closures made of glass (sometimes in combination with cork however), though sometimes porcelain, ceramic, metal, or hard rubber are used. Bender (1986) defined a stopper as "A closure held in place by means other than gravity and engaged primarily within the vessel bore." A simple cork is, of course, a type of stopper.

This section briefly covers various types of stoppers beginning with glass by itself, followed by glass and cork combinations, then other non-glass materials. Since cork by itself was discussed separately above it is not addressed again here. Glazed crockery is often found as the "stopper" part of the Lightning-type closures which was also covered above. Canning or fruit jar stopper type lids are discussed later on this page.

Glass

Glass

Excluding cork and crockery, a glass

stopper was likely the most common material that was used as a

bottle stopper, that that perception could be skewed by the higher likelihood of

a glass stopper surviving to the present than most other materials.

Glass stoppers can be either solid glass (two stoppers below) or hollow (green

stopper to the left). The

configuration and shapes of glass stoppers vary widely from the simple

utilitarian (two stopper below) to the ornate and decorative - like on the

decanter pictured to the left below). Click

W. T. Co. 1880 catalog page to see an illustration of available stock glass stoppers for various

types of bottles from the 1880 Whitall, Tatum & Company catalog (Whitall

Tatum Co. 1880). Some glass stoppers were designed for disposable

bottles like the club sauce bottle stoppers pictured below which had the shank

of the stopper sheathed in cork (see the "Glass & Cork" discussion below).

Other stoppers were intended for re-useable or decorative bottles like the

colorless glass decanter below. Regardless of the shape of the

stopper, they were all intended to perform the same function - insert securely

in the neck of a bottle and seal the contents from evaporation, oxidation,

and/or contamination.

Glass

stoppers are made up of three parts - the shank, which is the part that

inserts into the bore/neck of the bottle; the finial which is the portion

above the shank that one grasps to remove the stopper from the bottle; and the

neck, which is the transition point between the shank and finial.

Click on the emerald green bottle above to view a larger picture of this bottle

illustrating these parts.

Glass

stoppers are made up of three parts - the shank, which is the part that

inserts into the bore/neck of the bottle; the finial which is the portion

above the shank that one grasps to remove the stopper from the bottle; and the

neck, which is the transition point between the shank and finial.

Click on the emerald green bottle above to view a larger picture of this bottle

illustrating these parts.

Most glass stoppers were molded to shape then the shank ground to a more precise shape. However, some very early bottles and decanters (first half of the 19th century and before) were free-blown or pattern-molded with the stopper shank (and matching bore) not molded or ground to shape (McKearin & McKearin 1941). If a more or less airtight seal was desired (and it usually was and is) then the shank of the stopper had to be ground down to precisely fit the bore of the bottle. The bore was also ground to the accept the stopper shank. The two ca. 1890-1910 glass stoppers pictured to the above right have the shanks ground to fit the bore of the bottles they were intended for. Since the stopper was ground to fit the neck of a specific bottle, each stopper is a relatively unique fit to a specific bottle. If the shank of the stopper and bore of the bottle show no evidence of shape grinding it is likely a bottle or jar intended to hold some type of dry substance, the grinding evidence was polished away (discussed below), or the shank of the stopper was originally fit with a strip of shell cork to ensure a seal (Jones & Sullivan 1989). See the "Glass & Cork" discussion below.

The emerald green bottle pictured

at the beginning of this section is a small smelling salts or

cosmetic bottle with a ground glass stopper that likely dates from the early

1900s, though could be from as late as the 1920s as it is a

"specialty"

bottle that is hard to precisely date. This small bottle is

mouth-blown in a three-mold as indicated by the absence of mold seams on the

bottle body

except right at the junction between the upper body and the narrow shoulder.

This bottle may or may not have been intended for re-filling and re-use, though

many of these type bottles were purchased and kept indefinitely because of their

decorative appearance - an example of attractive packaging selling the

product.

The emerald green bottle pictured

at the beginning of this section is a small smelling salts or

cosmetic bottle with a ground glass stopper that likely dates from the early

1900s, though could be from as late as the 1920s as it is a

"specialty"

bottle that is hard to precisely date. This small bottle is

mouth-blown in a three-mold as indicated by the absence of mold seams on the

bottle body

except right at the junction between the upper body and the narrow shoulder.

This bottle may or may not have been intended for re-filling and re-use, though

many of these type bottles were purchased and kept indefinitely because of their

decorative appearance - an example of attractive packaging selling the

product.

The modern (1990s) mouth-blown specialty decanter pictured to the left was produced to hold some of the world's most expensive liqueur - Remy Martin Louis XIII Grande Champagne Cognac , which is engraved on the real gold neck collar. The attention to detail on this expensive to produce bottle is evidenced in that it has a ground glass stopper and bore where the grinding evidence was polished away. Click Remy Martin stopper for a close-up picture of the stopper which shows no obvious evidence of the grinding it did receive. (These type expensive decanters, though produced primarily to sell the even more expensive contents, were (and are) intended to be re-used and are rarel thrown away. These decanters even have the etched signature of the glassmaker as well as what number bottle it was of the production.)

Glass stoppers of varying shapes and sizes were utilized in a wide array of different type bottles over a very long period of time. Because of that fact there are few dating opportunities inherent with glass stoppers. Other manufacturing based diagnostic features must be used to date a bottle with a glass stopper. Glass stoppers are most common in bottle types that were intended to be either re-filled/re-used or the original contents utilized over a long period of time. This includes: perfume bottles, bulk chemicals and pharmaceutical product bottles and jars, liquor and wine bottles/decanters, some non-perishable food type bottles, and many inkwells.

Glass stoppers are rarely if ever seen in the majority of bottle types where the contents were intended to be consumed all at once, the contents were incompatible with glass stoppers, and/or the bottle was intended to be thrown quickly away (most bottles). Bottles with ground glass stoppers were 2 or 3 times more expensive than the equivalent bottle without a glass stopper so it is not surprising that most bottle types never or rarely were made with glass stoppers. This larger group of bottle types includes: most all patent/proprietary medicines and bitters; druggist bottles; beer, soda/mineral water, and champagne bottles (glass stoppers are not compatible with carbonation); food bottles; milk bottles; most ink bottles; and most liquor, wine, and champagne bottles (Jones & Sullivan 1989).

Glass

& Cork

Glass

& Cork

A

very common category of bottle stoppers merged cork and glass in combination. The

shank of the glass stopper was molded to shape, like most of the glass stoppers described above, but neither the shank nor the bore of the bottle were

ground to mesh with each other. Instead, a cork sheath (a cork with a

hollow center called "shell cork" in the trade) was placed around

the stopper shank allowing for a tight seal of the bottle because of

the pressure of the glass stopper shank against the shell cork which pressed against

the bore of the bottle. This is shown in the picture to the left and the

illustration below. The use of cork in combination with a simple glass

stopper was much cheaper than hand ground glass stoppers (Illinois Glass Company

1920). This type of closure is often called the "shell cork and stopper"

style.

A very common configuration of the glass and cork combination closure were the club

sauce type stoppers, several of which are pictured below right without their shell cork sheaths

which deteriorated long ago. This

type stopper has a flat, circular, horizontal top portion (finial) with a narrow tapered shank

on the underside perpendicular to the finial; there is no neck between the

finial and the shank. This conformation of stopper was also called a

"flat hood" stopper (Whitall Tatum & Co. 1902). A diagnostic feature of a

finish that accepts a club sauce type stopper is that just inside of the bore,

about 1/2" below the finish rim, there is a distinct ridge or cork seat surface

on which the cork rests. This gives rise to the alternative name for this

finish/closure of a "stopper and cap seat" (Boow 1991). The

picture to the left above shows a club sauce type stopper in the bore of a more or

less "mineral" type finish with

the cork still present and encircling the stopper shank, though the cork is

actually adhering to the walls of the bore. Click and enlarge this

picture as the cork seat ledge is just slightly visible right where the lower

edge of the cork shell ends. With the cork and stopper missing, the cork seat ledge

can be seen or easily felt by sticking ones finger in the bore. Be aware

that not all bottles that originally had a club sauce type stopper have this ledge, but

bottles/finishes with a cork seat ledge present were made for this type of closure.

When opening these type bottles, it is not clear if the cork was intended to remain around the

stopper shank or remain in the bore of the bottle; probably both ways depending

on the product.

A very common configuration of the glass and cork combination closure were the club

sauce type stoppers, several of which are pictured below right without their shell cork sheaths

which deteriorated long ago. This

type stopper has a flat, circular, horizontal top portion (finial) with a narrow tapered shank

on the underside perpendicular to the finial; there is no neck between the

finial and the shank. This conformation of stopper was also called a

"flat hood" stopper (Whitall Tatum & Co. 1902). A diagnostic feature of a

finish that accepts a club sauce type stopper is that just inside of the bore,

about 1/2" below the finish rim, there is a distinct ridge or cork seat surface

on which the cork rests. This gives rise to the alternative name for this

finish/closure of a "stopper and cap seat" (Boow 1991). The

picture to the left above shows a club sauce type stopper in the bore of a more or

less "mineral" type finish with

the cork still present and encircling the stopper shank, though the cork is

actually adhering to the walls of the bore. Click and enlarge this

picture as the cork seat ledge is just slightly visible right where the lower

edge of the cork shell ends. With the cork and stopper missing, the cork seat ledge

can be seen or easily felt by sticking ones finger in the bore. Be aware

that not all bottles that originally had a club sauce type stopper have this ledge, but

bottles/finishes with a cork seat ledge present were made for this type of closure.

When opening these type bottles, it is not clear if the cork was intended to remain around the

stopper shank or remain in the bore of the bottle; probably both ways depending

on the product.

The flat top portion of the glass stopper

often has embossing on it identifying

the product brand - virtually always a sauce product. The most commonly found embossed stopper is from the

Lea & Perrins® Worcestershire sauce bottles, which began importation

into the U.S. in 1849. The picture to the right shows one stopper (facing towards the

camera; click to enlarge) which is embossed Garton's, an English competitor of the Lea & Perrins®

company. Garton's began production of their HP Sauce in 1903 giving

an earliest possible date for this particular stopper. In 1930, HP acquired

ownership of Lea &

Perrins® and both products are still produced by the same company (HP Foods Ltd.

which was recently acquired by H. J. Heinz).

Embossed Lea & Perrins® stoppers can date back to the third

quarter of the 19th century, as is likely of the various competing sauces.

The flat top portion of the glass stopper

often has embossing on it identifying

the product brand - virtually always a sauce product. The most commonly found embossed stopper is from the

Lea & Perrins® Worcestershire sauce bottles, which began importation

into the U.S. in 1849. The picture to the right shows one stopper (facing towards the

camera; click to enlarge) which is embossed Garton's, an English competitor of the Lea & Perrins®

company. Garton's began production of their HP Sauce in 1903 giving

an earliest possible date for this particular stopper. In 1930, HP acquired

ownership of Lea &

Perrins® and both products are still produced by the same company (HP Foods Ltd.

which was recently acquired by H. J. Heinz).

Embossed Lea & Perrins® stoppers can date back to the third

quarter of the 19th century, as is likely of the various competing sauces.

The

club sauce type glass stopper/cork combination closures were also used on an

assortment of different, non-sauce types of bottles from the mid-19th

century through the mid 20th century. They were quite commonly used on

mouth-blown liquor flasks and some larger cylinder liquor bottles from the

late 19th century (primarily 1890s) into the mid 1910s. They were also used

after that time on machine-made liquor flasks into Prohibition ("medicinal"

liquor) and likely through the 1920s and possibly later. Many of the liquor bottles

that used the club sauce type stopper/cork are identifiable in that the inside of the bore has

the cork seat ledge in evidence. Click

IGCo. 1908 catalog page for an illustration excerpt from the 1908 Illinois Glass Company

catalog showing a couple flasks with club sauce type stoppers in place.

This closure was occasionally used on some

larger sized, mouth-blown, patent/proprietary medicine bottles from the late

19th to early 20th century. The tooled "reinforced extract" finish to the

left with the glass stopper in place is

on an

Oregon Blood Purifier (Portland, OR) bottle that dates from the 1890s.

This bottle has the distinctive and diagnostic cork seat ledge on the inside

of the bore.

The

club sauce type glass stopper/cork combination closures were also used on an

assortment of different, non-sauce types of bottles from the mid-19th

century through the mid 20th century. They were quite commonly used on

mouth-blown liquor flasks and some larger cylinder liquor bottles from the

late 19th century (primarily 1890s) into the mid 1910s. They were also used

after that time on machine-made liquor flasks into Prohibition ("medicinal"

liquor) and likely through the 1920s and possibly later. Many of the liquor bottles

that used the club sauce type stopper/cork are identifiable in that the inside of the bore has

the cork seat ledge in evidence. Click

IGCo. 1908 catalog page for an illustration excerpt from the 1908 Illinois Glass Company

catalog showing a couple flasks with club sauce type stoppers in place.

This closure was occasionally used on some

larger sized, mouth-blown, patent/proprietary medicine bottles from the late

19th to early 20th century. The tooled "reinforced extract" finish to the

left with the glass stopper in place is

on an

Oregon Blood Purifier (Portland, OR) bottle that dates from the 1890s.

This bottle has the distinctive and diagnostic cork seat ledge on the inside

of the bore.

Club sauce type stoppers were uncommon on types of bottles outside of those

noted, but were likely used occasionally on virtually any type bottle intended

to hold non-carbonated substances. These stoppers

are very commonly excavated from sites intact since they have no weak spots to break

like the "neck" of the regular glass stoppers noted earlier (Jones & Sullivan 1989).

No embossed club sauce type stoppers are known to the author from any product

but sauce bottles; all of the stoppers used in medicines and liquor bottles were

apparently unmarked.

Club sauce type stoppers were uncommon on types of bottles outside of those

noted, but were likely used occasionally on virtually any type bottle intended

to hold non-carbonated substances. These stoppers

are very commonly excavated from sites intact since they have no weak spots to break

like the "neck" of the regular glass stoppers noted earlier (Jones & Sullivan 1989).

No embossed club sauce type stoppers are known to the author from any product

but sauce bottles; all of the stoppers used in medicines and liquor bottles were

apparently unmarked.

Another relatively common configuration of the glass and cork closure type - particularly in bottles of English origin - is the larger shell cork and stopper style used on relatively wide mouth food bottles. It is functionally similar to the club sauce style described above - including the matching cork seat ledge inside the finish for placement of the closure - but much larger. The image to the right is of a Mellin's Infant's Food bottle dating from the 1890s to early 1900s, although this style of closure dates back to at least the early 1850s (Boow 1991). Click on the following link - close-up of the finish - which shows the shell cork still stuck in place on the ledge within the bore/mouth of the bottle but with the glass stopper removed. (This bottle style is described in more depth at this link: Baby Food Bottles.)

The

other relatively common glass and cork combination

stopper was the peg stopper. It was similar in application to the club sauce

stopper

except that the shank was straight (not tapered) and the finial portion was

taller and very often ornate. The shank of the peg stopper was frequently

molded with ridges or threads in order for the shell cork to firmly attach to

the shank. This likely helped keep the shell cork from sticking in the

bore of a bottle when the closure was removed. However, some authors

believe that the cork was intended to remain in the bore of the bottle with

access to the contents achieved by unscrewing the stopper from the cork (Jones &

Sullivan 1989). It seems likely that the screw threaded peg stoppers were

intended to be pulled out with the cork attached and the smooth shank version intended to

pull out leaving the cork behind.

The

other relatively common glass and cork combination

stopper was the peg stopper. It was similar in application to the club sauce

stopper

except that the shank was straight (not tapered) and the finial portion was

taller and very often ornate. The shank of the peg stopper was frequently

molded with ridges or threads in order for the shell cork to firmly attach to

the shank. This likely helped keep the shell cork from sticking in the

bore of a bottle when the closure was removed. However, some authors

believe that the cork was intended to remain in the bore of the bottle with

access to the contents achieved by unscrewing the stopper from the cork (Jones &

Sullivan 1989). It seems likely that the screw threaded peg stoppers were

intended to be pulled out with the cork attached and the smooth shank version intended to

pull out leaving the cork behind.

The illustration to the left above is from a ca. 1905-1910 Bellaire Bottle Company catalog showing ornate peg stoppers with both threaded and unthreaded shanks. Click Bellaire catalog page for a full page illustration from the Bellaire catalog which includes peg stoppers, with and without threads, as well as regular ground glass stoppers. Peg stoppers appear to have been most commonly used in toiletry, perfume, and cologne bottles during the late 19th through at least the first third of the 20th century. Click I.G.Co. 1920 catalog page for an illustration from a ca. 1920 Illinois Glass Company catalog that shows some of their relatively ornate peg stoppers and notes their intended use with shell corks.

Metal & Cork

Metal & Cork

Sprinkler,

squirt, and tube tops (called a "sprinkler" closure or stopper here) were a common

stopper type on

various types of bottles

from the mid-19th century up until at least the mid-20th century. The

picture to the right shows several open type sprinkler tops from a 1920 Illinois Glass Company

catalog.

Sprinkler,

squirt, and tube tops (called a "sprinkler" closure or stopper here) were a common

stopper type on

various types of bottles

from the mid-19th century up until at least the mid-20th century. The

picture to the right shows several open type sprinkler tops from a 1920 Illinois Glass Company

catalog.

The sprinkler stoppers are different in design and quite different in utility from the glass and cork combination stoppers noted above. The sprinkler tops were made from metal and did not typically need to be removed from the bottle in order to use the contents; the contents were dispensed through the opening that ran through the entire closure. What the two types of stoppers had in common was that they inserted the same way into the bottle bore and were held in place by a shell cork wrapped stopper shank. Some sprinkler tops were open like the ones to the right; others had various types of caps or closures on the metal top. Click I.G.Co. 1920 catalog page to view an illustrated page of different types and styles of sprinkler tops from the 1920 catalog.

These types of closures were used on an assortment of different type bottles including cruets, sauce bottles, colognes, tooth powders, barbers' bottles, and some flavoring type bitters bottles (Jones & Sullivan 1989). The image to the left is of a sprinkler top in a late 19th to early 20th century mouth-blown barber bottle. Sprinkler tops were not used for carbonated beverages, nor most liquor or wine bottles. Unfortunately, due to the wide span of use, there are no diagnostic dating opportunities related to this type of closure; the manufacturing related physical features of the bottle itself must be used. Because of the composition of these type stoppers, they are not frequently found intact on historic sites as they usually deteriorated.

Rubber & other materials

Rubber, wood, paper, wax, corn cobs, and

other materials were

occasionally used as general closures on bottles, particularly during the

earlier portion of the period covered by this website (early 19th century).

There is not much to say about them since there is little inherently

datable about these materials as closures and most were organic substances that

did not survive the ravages of time that a glass bottle will weather with ease.

Rubber stoppers are one exception in that they appear to have been primarily used during the first half of the 20th century and possibly even to the present in some specialty situations (chemical reagent bottles). Most notably, rubber stoppers were common in Clorox® and Lysol® bottles during the 1920s and 1930s; bottles that are commonly found in sites that date from the Depression era. Undoubtedly they were used for other products but the information on such is sparse at this time. Click Toulouse's early closures quote to jump back to the brief discussion of early and unusual closures found at the beginning of this "General Closures" section.

OTHER GENERAL CLOSURE TYPES

There were a plethora of other closure types that received some variable

application on different types of bottles. Below are several types of

non-threaded metal caps that found varying acceptance and use with some bottle dating related utility.

Just be aware that the closures discussed briefly here are but a small sampling

of the variety of non-threaded metal closures invented and used during the last

couple decades of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century.

Non-threaded metal caps

Non-threaded metal caps

There

were a wide variety of metal caps used for closures on many

types of bottles and jars. Metal caps found particular utility on bottles/jars having a wide mouth or bore in order to access

(or insert) the contents, though metal caps of various types were also commonly

used for bottles with smaller openings (aka smaller mouth or bore). Fruit or canning jars are the most well known type

of glass container that utilized metal lids (covered later on this page).

Many types of food bottles, ointment jars, some snuff bottles, some

medicinals, and occasional other types of bottles utilized metal

caps for closure (Lief 1965).

The

wide variety and

very wide time span of use of metal caps (still used today) limits its utility for any dating refinement

of historic bottles unless the finish itself was specific to a particular

closure that had particular time span of use. Typically however, the manufacturing based diagnostic

features of the bottle or jar itself must be interpreted in arriving at an approximate date range. In addition, the metal caps for many 19th

and early 20th century bottles/jars

are rarely found intact and identifiable on historic sites since the metal

usually rusted away unless never buried or discarded in very dry areas like many parts of the American

West.

The

wide variety and

very wide time span of use of metal caps (still used today) limits its utility for any dating refinement

of historic bottles unless the finish itself was specific to a particular

closure that had particular time span of use. Typically however, the manufacturing based diagnostic

features of the bottle or jar itself must be interpreted in arriving at an approximate date range. In addition, the metal caps for many 19th

and early 20th century bottles/jars

are rarely found intact and identifiable on historic sites since the metal

usually rusted away unless never buried or discarded in very dry areas like many parts of the American

West.

One commonly used generic cap was as illustrated to the above left in the Whitall Tatum & Co. (Millville, NJ with offices in New York, NY and Philadelphia, PA.) catalog from 1880. These type of caps were held in place by friction and/or gravity and did not provide an air tight seal. The amber jar pictured to the right above is a possible Whitall Tatum & Co. product from that era that is virtually identical in shape to the ointment pots shown in the illustration which were noted as available in amber glass. (The illustration also notes that glass lids were also available instead of metal, though significantly more expensive.) This pictured small amber jar is mouth-blown in a cup-mold and has a ground rim. Cup-bottom molds were used on smaller bottles like this as early as the 1870s; ground lips or rims go back at least that early, so the diagnostic features of the bottle do fit the catalog date. However, non-threaded lids on bottles and jars were used for an lengthy period of time so that even on a mouth-blown bottle like pictured, it is possible that it could date as late as the 1910s. (Note: From the context the pictured ointment jar was found it most likely dates from the 1880s.)

Two of the more popular band caps were the Goldy Seal and the Phoenix Cap; both of which are covered later on this page.

Kork-N-Seal

cap

Kork-N-Seal

cap

The Kork-N-Seal cap was a closure designed to provide for the

easy resealing of

bottled liquid products. It is essentially a re-usable crown cap, though

it was also used in larger sizes that fit bottles with a bore larger than the

approximate 5/8"

of a crown finish bottle, e.g., 1" and 1¼" (IGCo. 1911; Caniff 2015). The finish

rim that

typically accepts the Kork-N-Seal cap looks like the upper "bead" part of crown finish. The collar

or lower part below the bead varied in shape

and was largely decorative as it was not related to the sealing of the cap

(Jones & Sullivan 1989). This closure worked by placing the cap on

the finish of the bottle and pulling down on the side toggle or lever. This pulled

on both ends of a metal wire loop that runs around the entire skirt of the cap,

tightening the skirt into the groove underneath the bead (picture below).

This closure is also referred to as a "lever" type (Berge 1980).